The Abuse of EBITDA

James A. Kyprios / Originally Published at www.securitiesexpert.org/ on May 6, 2022

(I want to thank investment banking expert Bill Purcell (www.purcellbanking.com) and Joe Loffredo, CFO at China Merchants Bank’s branch in New York City, for their suggestions in writing this article.)

Introduction

I am not an accountant, but I am a trained financial analyst. There was a time many years ago when I would spend hours reviewing ten years of historical financial statements. I would take out my pencil and eraser and put the relevant numbers on large spread sheets. And I would then plug in my trusted (and huge) calculator which would grind out all the necessary sums and ratios I needed for my financial analysis. To make sure that I understood the financial history of the company, I would also carefully read all the footnotes in the annual reports. And most importantly, I would read the Auditor’s Opinion on each of the annual reports. It had to be an unqualified audit (“clean opinion”) with words from the external auditor to this effect: in our opinion the financial statements present fairly the balance sheet and income statement of the company in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles (“GAAP”).

Then I would go out and visit the company and meet with the top officers including the CEO and the Chief Financial Officer. I would have a list of questions, many based on my review of the historical statements. I would invariably take a plant tour in order to better understand the operations of the company. I would make an industry analysis, an analysis of the competition and would make sure to understand how the company reacted to external economic conditions. I would also make supplier, customer, competitor, and bank checks. I would not rely on credit ratings. As a matter of fact, the companies we would lend to in most cases did not have external ratings.

I have a special fondness for those days of real direct lending and thorough due diligence. However, those days no longer exist. Over time, much of corporate lending has evolved to the point where an agent bank puts together a loan package and sells it to investors, usually other banks, and other financial institutions. Investment decisions are now very often based on credit ratings which to a very great extent are based on a cursory review of the numbers.

Except the numbers have become so confusing now that only the most highly trained financial analysts even pretend to understand them. There has been a growing mistrust of GAAP not only among companies which are looking for money but also among many institutional investors. This has led to the wide use of so-called non-GAAP measures. The most prominent of these is EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization) which represents cash flow from operations; and EBITDA less capital expenditures which represents free cash flow (i.e., cash flow available to debt and equity investors). EBITDA is the key number because in recent years it has been the most important one used by the rating agencies to calculate financial leverage (Debt/EBITDA). This makes good sense because cash flow (and/or free cash flow) is an important metric for analysts and investors to understand. To make things even more confusing, adjustments to EBITDA (invariably increasing EBITDA) are now commonplace. Leverage is now very often defined as Debt/adjusted EBITDA.

There is no doubt that important investment decisions are made on the basis of non-GAAP numbers, but these non-GAAP numbers often are being abused and sometimes improperly manipulated.

Why the mistrust of GAAP impelling the use of non-GAAP measures? This and related matters are explored in detail in this article. My conclusion is that the accounting profession can no longer ignore non-GAAP measures. It needs to opine on whether the calculation of adjusted EBITDA is in accordance with agreed-to methodologies and whether or not adjusted EBITDA is materially misleading.

Some reforms are needed as I have attempted to point out in this article. There is a lot of “detail” in this article, but I hope you agree that understanding this topic in worth the effort.

Accounting is the Language of Business

“Accounting is the language of business.” I have been told this many times. But sophisticated accounting systems are not necessary for very small businesses which can be evaluated by their cash flow which is easy to count. The bigger the business, the more complicated it is. Evaluating a large business requires at least a cursory understanding of “the numbers.” And yet, we see many examples of members of the C-Suite (CEOs, CFOs, COOs, CIOs, etc.) and Board Members who do not have a solid grasp of accounting.

We now live in an age where most investors (whether they be bank lenders or owners of public shares and bonds) do not have direct access to the companies they invest in. They therefore must rely to a great extent on “the numbers.” Accounting is crucial for an understanding of a company’s past and present positions as well as its prospects. Accounting is also very important for the rating agencies who grade the degree of credit risk in a company’s debt instruments. In addition, accounting is important for equity analysts who try to assess whether shares are overvalued or undervalued.

Here is what the Auditor of Microsoft has to say in its Opinion for Fiscal Year 2021 (Microsoft is one of only two companies with a AAA rating, the other being Johnson and Johnson):

We have audited the accompanying consolidated balance sheets of Microsoft Corporation and subsidiaries (the “Company”) as of June 30, 2021 and 2020, the related consolidated statements of income, comprehensive income, cash flows, and stockholders’ equity, for each of the three years in the period ended June 30, 2021, and the related notes (collectively referred to as the “financial statements”). In our opinion, the financial statements present fairly, in all material respects, the financial position of the Company as of June 30, 2021 and 2020, and the results of its operations and its cash flows for each of the three years in the period ended June 30, 2021, in conformity with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America.” (Emphasis added).

We have also audited, in accordance with the standards of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (United States) (PCAOB), the Company’s internal control over financial reporting as of June 30, 2021, based on criteria established in Internal Control — Integrated Framework (2013) issued by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission and our report dated July 29, 2021, expressed an unqualified opinion on the Company’s internal control over financial reporting. (Emphasis added).

Basis for Opinion

These financial statements are the responsibility of the Company’s management. Our responsibility is to express an opinion on the Company’s financial statements based on our audits. We are a public accounting firm registered with the PCAOB and are required to be independent with respect to the Company in accordance with the U.S. federal securities laws and the applicable rules and regulations of the Securities and Exchange Commission and the PCAOB.

We conducted our audits in accordance with the standards of the PCAOB. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the financial statements are free of material misstatement, whether due to error or fraud. Our audits included performing procedures to assess the risks of material misstatement of the financial statements, whether due to error or fraud, and performing procedures that respond to those risks. Such procedures included examining, on a test basis, evidence regarding the amounts and disclosures in the financial statements. Our audits also included evaluating the accounting principles used and significant estimates made by management, as well as evaluating the overall presentation of the financial statements. We believe that our audits provide a reasonable basis for our opinion.

To recap: The auditor is not responsible for the preparation of the financial statements; the company is. The auditor follows what are referred to as Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (“GAAP”) in auditing the financial statements and notes to the financial statements. It is the auditor’s job to reasonably determine that the statements are free of material misstatements as a result of effective controls by the company in preparing the statements. Also, and this is important, the language in this Opinion is fairly standard and what is produced is an “unqualified audit” or “clean opinion.” This clean opinion also covers the company’s internal control over financial reporting.

How relevant is GAAP to shareholders and creditors?

Years ago, the answer to this question was that such an opinion was very relevant. But things have changed over time. Over the years, I have witnessed the growth of accounting pronouncements to the point where it is becoming increasingly difficult for even a trained financial analyst to understand the reports and come to a good conclusion as to the credit worthiness and prospects of many companies.

In my opinion, this in good part is due to the establishment and prominence of the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), a private sector, not for profit organization which establishes financial accounting and reporting standards for public and private companies in accordance with GAAP. FASB is recognized by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the American Institute of CPAs (AICPA) as well as state Boards of Accountancy as authoritative. FASB makes the accounting rules which auditors must follow.

I recall that in the late 1960s, FASB only had a handful of major pronouncements. Now there are many more, probably more than 1000, which are known as Accounting Standards Codifications (ASCs). I recall that when I was beginning my career that FASB came out with a new rule then called FASB 7 which related to capitalization of leases. I am not an accountant but as a financial analyst this struck me as a bit of a stretch.

Here is how it works. Suppose you have two similar companies and one owned most of its buildings while the other one leased the buildings. The accounting used to be quite simple. The company that owned the buildings would invariably have mortgages on the properties. The balance sheet would show the buildings at cost (less depreciation) and liabilities would include the mortgages. Expenses on the income statement show depreciation (a non-cash item) of the building as well as any cash expenses such as maintenance and interest on the mortgage.

The similar company which leased rather than owned the properties would have nothing on its balance sheet to reflect the buildings and would have no liabilities on its balance sheet except for accrued rental expenses. The income statement would include rental expenses.

The members of FASB thought that this was not fair because the company renting the properties would be understating the risk of the company by leasing. In the eyes of FASB, the two companies were similar. It made a distinction between finance leases (which were to be capitalized on the balance sheet) and operating leases (which were not to be capitalized). The later were short term leases. The former were longer term leases and simply an alternative to buying the buildings or equipment out right.

FASB’s solution was to pass a rule (FASB 7) which required the company leasing properties and equipment to capitalize the leases. In other words, for accounting purposes, the balance sheet would have to show a (phantom) asset of the assumed value of the leased building as well as a (phantom) liability representing a mortgage. In FASB’s eyes this was necessary to more nearly reflect the risks involved. The income statement would show phantom interest expense and depreciation as if the company really did own and mortgage the properties. I remember that many of us mocked these types of changes and said that these academics are muddying the waters.

Another example of an important FASB pronouncement was the desire to capture the effect of future health care costs on a company. It just so happens, if memory serves me correctly, that General Motors was severely penalized by this latest pronouncement. When the FASB pronouncement came into effect in the early 1980s, GM would have had a profit for the relevant fiscal year. However, it had to take a huge one time write off to reflect a new liability on its balance sheet based on the present value of future (assumed) health care costs of the company. Without this new accounting rule, GM would have shown a profit; but with the new accounting rule, it showed what at the time was a shockingly huge loss. As a result of this one time “write off,” General Motors recorded one of the highest losses in U.S. history. The health care charge was about ten times the size of the company’s normal profitability. This left such an impression on so many people that many in the business community realized that perhaps reported Net Income was not the most important figure indicating a company’s profitability. Is it any wonder that companies started resorting to non-GAAP measures to tell their story?

It is obvious that financial statements were being converted from reflecting hard reality to reflecting economic and financial theories of the FASB.

Then, derivatives come on the scene. The FASB pronouncements came up with rules that few understand making it almost impossible for someone who is not an expert in derivatives to understand the financial statements. The former head of Citi Corp, Sandy Weill, was joking once that he decided to retire because he was not smart enough to understand derivatives. This means that he could no longer understand the financial statements of the company he was running.

Finally, there is the recent case of what is known as CECL (Current Expected Credit Losses). This idea, believe it or not, requires a bank to reserve up front for credit losses when it makes a loan. One of my friends who has many years of experience commented: “Who would ever want to make a loan if they thought they would lose money on it?” People defending FASB’s decision to implement CECL say that CECL should be looked at from a portfolio point of view not from an individual loan point of view. Perhaps.

When CECL was implemented by banks in the beginning of 2020, the methodology led to significantly over reserving for bad loans and by the end of the year, they had to reverse some of these reserves which led to unexpected increases in profitability in 2020 and in early 2021.

The basic idea behind the foregoing stories and comments is to point out that it is understandable that many investors (creditors and shareholders) in companies would lose confidence in the accounting profession. This is a serious problem. For example, it is quite well known that CECL is not (to put it very diplomatically) admired by the banking profession. To be more blunt, some bankers think CECL is nonsense.

The distortion of CECL on Net Income was amply demonstrated this month when JP Morgan Chase, the largest bank in the U.S released its quarterly earnings. Fiscal year 2022 first quarter results were $8.3 billion, down 42% from fiscal year 2021 first quarter results of $14. 3 billion. Credit reserves under the CECL rules increased by $900 million in the latest quarter compared to a release of credit reserves of $5.2 billion in last year’s first quarter. In other words, the reserve expenses were about $6.1 billion higher in this year’s first quarter than in last year’s. These are not cash expenses. They are book expenses mandated by CECL and this is the primary reason JP Morgan’s earnings were significantly off this year. The earnings announcement in turn caused a drop in JP Morgan’s stock price despite the fact that earnings for the latest quarter exceeded expectations.

CECL came into effect in 2020 when the onset of Covid made it appear that the economy would greatly suffer. JP Morgan and other banks made large increases in the loan reserves in 2020, but by the end of the first quarter in 2021, it became obvious that the economy was very strong as a result of actions by the Fed and the Government to prop up the economy. Since loan loss reserves now appeared to be way too high, the bank drastically decreased loan loss reserves in the first quarter of 2021 by $5.2 billion. This was a one shot increase in first quarter 2021 earnings which could not be repeated in next year’s first quarter earnings. In the first quarter of 2022, with the possibilities of economic troubles due to the war and tightening by the Fed to ward off inflation, JP Morgan Chase had to increase its loan loss reserves.

Once again, these are book entries in good part mandated by a system imposed on the banks on how to reserve for future possible loan losses. CECL differs from previous loan reserve methods by assuming extensions of credit to be riskier upfront thus compelling banks to create reserves at the time of extensions of credit. As demonstrated in the recent JP Morgan first quarter 2022 announcement, this may unwittingly lead to wilder earnings swings than before. The rule creates greater variability in earnings and in stock prices on the basis of questionable assumptions about the future.

In addition, annual reports have gotten so long and are so complicated that it is becoming more and more difficult for the laymen to read much less absorb what is being said. Suppose that you are an analyst at a financial institution in charge of (say) 20 companies. You have to review annually 20 reports, each with over 100 pages of dense business and financial material, not to mention quarterly income reports for each of your portfolio companies.

It is not a secret that many people (companies and investors) no longer think that the famous “bottom line” entitled Net Income is not such a meaningful figure anymore. These borrowers and investors do not really believe that Net Income represents the true profitability of a company.

Very simply, we now live in a world where those teaching and practicing finance and running companies often have dismissed the importance of accounting and in some cases now think it is irrelevant. There are now MBA programs which no longer require students to take accounting courses. I have even heard, in person, a highly regarded Harvard Professor of Finance, dismiss the importance of accounting. He said that what is important is cash flow analysis and not many of the esoteric theories of the accounting profession. He said that there is a basic distrust of GAAP accounting. What is important is cash flow analysis. It is interesting that he has never put these sentiments in writing.

Mistrust of accounting is a very unfortunate situation. Most, if not all transactions, which take place in a company (whether sales, expenditures of any kind, financing arrangements and so on) must be reflected in an accounting transaction which leads to the creation of financial statements. I have found over the years that I cannot really understand much about a company unless I grind the numbers. This leads to understanding in some cases and questions in other cases.

And yet, I do grasp how more and more CEOs, CFOs, etc. believe that GAAP numbers do not give an adequate understanding of a business. I believe that the use of non-GAAP numbers in many cases is an honest attempt to explain a business given the perceived inadequacies of GAAP.

The problem with non-GAAP numbers is that they sometimes can and are either manipulated or used to mislead or misinform the investors.

What exactly are GAAP metrics?

Before discussing the results of the disenchantment with accounting as spelled out above, we need to understand what exactly GAAP metrics are and also note that auditors cannot render an opinion on non-GAAP metrics.

GAAP metrics include everything that appears in a balance sheet, income statement and the statement of cash flow. On the balance sheet, this includes all the assets and all the liabilities and net worth items. On the income statement this includes sales, cost of goods sold, gross profit, overhead expenses, depreciation, interest, and taxes. On the cash flow statements this includes items generating and reducing cash from operations, items related to capital expenditures and items related to financing including repayment of debt. In addition, GAAP metrics include everything that appears on the statement of equity and the statement of comprehensive income. These last two statements provide additional detail to balance sheet items comprising equity (or net worth).

To recap: GAAP metrics are only those metrics which appear on the three components of financial statements: the balance sheet, the income statement, and the cash flow statement. Metrics derived from these metrics, but not explicitly seen on the financials, are non-GAAP measures. A very simple and common example of a non-GAAP metric should suffice.

EBITDA(1) is the most commonly used non-GAAP metric

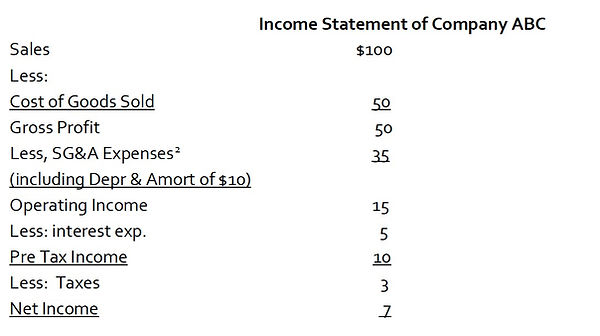

Here is how EBITDA is derived from GAAP metrics.

Please note that Net Income and Operating Income are GAAP metrics. EBITDA, which is nowhere mentioned on the income statement, is not. Here is how EBITDA is calculated (or derived) from the income statement.

Another way of calculating EBITDA in this case is to add Depr & Amort of $10 to Operating Income of $15.

The accounting profession treats GAAP metrics as more legitimate than non-GAAP metrics and the auditors are very careful to point out that they are only giving a “clean opinion” (also referred to as an unqualified audit) on statements which contain GAAP metrics- again, the balance sheet, the income statement and the cash flow statement.

__

1 Defined on page two as Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization

2 SG&A stands for selling, general and administrative expenses. In other words, overhead

Why is EBITDA so important?

It is now generally recognized in the business and investment community that the most important elements in evaluating a company’s performance are not GAAP metrics such as Net Income and Equity.

There are countless examples of companies which show losses and/or have a deficit Net Worth which are vibrant and healthy companies. It used to be thought that a company with a negative Equity (also called Net Worth) was a bankrupt company. But this ignored the fact that assets of a company in general were conservatively valued under GAAP (they are mostly valued at lower of cost or market with some exceptions). What is often more important now is the market value of the equity. It also used to be thought that Net Income was indicative of a company’s profitability; but a more accurate statement is that Net Income is a company’s book profitability based on a host or assumptions under GAAP. What is really important is the company’s cash flow from its business operations (before taking into account money spent on investments and any financing items). Many real estate companies show losses under GAAP but in fact are quite profitable on a cash basis. Private equity portfolio companies are usually evaluated by their owners on the basis of free cash flow (EBITDA minus capital expenditures), not on Net Income.

Companies do not go bankrupt because they are losing money on a book basis or because the books show a negative Net Worth. Companies go bankrupt when they run out of cash and cannot meet their obligations. Therefore, GAAP metrics, it must be acknowledged, do not tell the whole story.

Over the years, there has evolved general agreement in the financial community including the rating agencies that EBITDA (once more—Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization) is good proxy for the profitability of a company. EBITDA is supposed to represent the cash flow generated by a business. Academics for the last sixty years have taught that the real value of a company is the discounted cash flow from operations of a company.

The rationale for using EBITDA is that it gives us an easy way to compare companies’ business performances. As noted, EBITDA stands for Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization. Net Income figures are adjusted by adding back taxes (which can vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction and from industry to industry and also from the cleverness of accountants); and by adding back interest (thus comparing companies irrespective of leverage); and by adding back depreciation and amortization (which can also vary based on accounting rules and the discretion of management). EBITDA fits in perfectly well with the Modigliani and Miller Theory (“M&M”) which has been taught in universities and graduate schools for over 60 years. M&M postulates that the value of a company is not based on its capital structure but instead on the discounted cash flow of a company’s business operations. EBITDA has therefore been universally accepted as a proxy for a company’s cash flow from operations.

Companies are bought and sold on the basis of multiples of EBITDA. In the last thirty years or so, the most important metric in evaluating a company’s credit worthiness is Total Debt/EBITDA. In today’s world this is universally considered as the leverage of a company.

Decisions are made by creditors, rating agencies and investors on the basis of EBITDA. And yet, EBITDA is not a GAAP number and is still viewed with suspicion by the accounting profession and regulators.

But now EBITDA is sometimes being abused

Companies are no longer content with EBITDA. There is now adjusted EBITDA and the adjustments are invariably additions to EBITDA and not subtractions. If EBITDA is increased through these adjustments, then the leverage as presently defined (Total Debt/EBITDA) decreases. If EBITDA is increased this means that the assumed valuation of the company would go up, ceteris paribus (“all other things being equal” as the economists like to say). It is obvious that companies have strong incentives to increase EBITDA by the vehicle known as adjusted EBITDA.

EBITDA, as previously noted, is a non-GAAP measure. Adjusted EBITDA is a non-GAAP measure to even a greater extent. The auditors do not express an opinion on adjusted EBITDA, nor do they express an opinion on EBITDA which is easily calculated based on GAAP metrics.

The rationale for making these adjustments to EBITDA is simple in concept. The company is attempting to show that some expenses are not recurring or not relevant. We are, after all, trying to determine a company’s “normalized” cash flow from its business operations. Adjusting EBITDA by removing anomalies should ideally result in an accurate picture of a company’s steady stream of cash flow which can be used for reinvesting in the business, servicing debt and giving a fairly predictable return to owners.

But, as the saying goes, the devil is in the details. There are expenses that should not be recurring, but it just turns out that they often are recurring. There are expenses that are in fact legitimate expenses, but the company may find some rationale to discount or even discard them. Some of these expenses may relate to transactions with affiliated companies or with merger and acquisition expenses, or even with executive compensation.

The Harvard Business Review, in an article (“How EBITDA Can Mislead” by Karen Berman and Joe Knight, November 19, 2009) makes the following observation: “When WorldCom started trending toward negative EBITDA, they began to change regular period expenses to assets so they could depreciate them. This removed the expense and increased depreciation, which inflated their EBITDA. This kept the bankers happy and protected WorldCom’s stock.”

Not only can EBITDA be manipulated but the methodology for calculating EBITDA can be changed so that one period cannot be adequately compared to a previous period as was the case with WorldCom.

It is obvious that adjusted EBITDA can be misleading. Lenders have not been oblivious to this and have put in covenants restricting the types and amounts of such adjustments. The SEC has also been involved with regulations which concern so-called “pro-forma adjustments” indicating what a company’s cash flow would look like after an acquisition or after a disposition. For example, a company could claim that it would have large cost savings as a result of redundancies arising from a merger. The pro-forma adjustments are made before such redundancies even occurred. It would not be obvious at the time of the adjustments when and by how much these redundancies would occur. The SEC stepped in with changes to Regulation S-X (the SEC’s accounting rules which govern SEC filings related to pro-forma reporting for acquisitions and disposition). These specified in detail what was and was not allowed in calculating adjustments to EBITDA. Unfortunately, these rules were relaxed effective January 1, 2021, by giving management considerable discretion in the methodology and calculation of the adjustments to EBITDA.

For more information, the reader is referred to “Regulation S-X Updated and the Pro-Forma EBITDA Add Back” by Carolyn Zander Alford, Craig Lee, and Matthew Roberts of King & Spaulding, dated May 24, 2021. Here is what they have to say:

‘Adjusted EBITDA’ is used in calculation of financial maintenance covenants and leverage ratios, which in turn often affect a number of highly negotiated credit provisions, including pricing and basket capacity for incurrence tests and restricted payments. Adjusted EBITDA takes the standard EBITDA metric but is revised to add-back (and eliminate the impact of) certain items that borrowers believe are unusual, non-recurring or not indicative of the borrower’s actual operating profitability. One such add-back, the pro forma cost-savings add back, permits borrowers to adjust EBITDA to take into account specific events or actions that may reduce expenses (or create synergies) on a recurring basis, including those that are projected to materialize following an acquisition or disposition (e.g., elimination of employee redundancies). How these cost-savings and synergies are verified, and the guardrails around what can and cannot be added back in the calculation of adjusted EBITDA are often heavily negotiated between borrowers and lenders. One such guardrail used in many credit agreements is to allow pro forma adjustments for acquisitions and dispositions consistent with Regulation S-X given the limitations on such adjustments prior to the recent amendments.

To make this very clear– the relied upon guardrail for controlling adjustments, Regulation S-X, has been substantially weakened by giving management significant discretion and therefore this trusted guardrail is now of limited use. Lenders are no longer protected from “broad management discretion.”

As of this writing, it is not clear what the SEC will do to mitigate these types of abuses. We do know from experience that many pro-forma cost savings never fully materialize.

Examples of Different types of EBITDA Abuses

It is known that EBITDA “add backs” are becoming more and more prevalent and that these “add backs” increase EBITDA by as much as 25% in many cases and even more in other cases.

Here is what is stated in A Pragmatist’s Guide to Leverage Finance–Credit Analysis for Below-Investment-Grade Bonds and Loans Second Edition by Robert S. Kricheff, Harriman House LTD, 2021 (see pages 61 and 62):

Many times, when a new issue of a bond or a loan is coming to market, the issuer and underwriter will try to use their definition of adjusted EBITDA. This has become increasingly common when an acquisition is involved and particularly when it is a leveraged buyout (LBO) done by a PE firm. In these cases, they will often include synergies that the buyer expects to get from combining the acquired company with other operations or expected cost savings that the new ownership expects to be able to accomplish after taking over the company. These are often referred to as add-backs. Sometimes these cost savings may already be completed, or they may take a few years to accomplish and involved cash payments to achieve these savings (such as severance pay if lay-offs are involved). However, the company usually includes all these cost savings as add-backs in their current calculation of adjusted EBITDA even if they have not been completed. There are several reasons for why they do this: 1) to show better cash flow numbers when marketing their bonds and loans to investors; 2) to give guidance to investors on what they believe the can accomplish with the acquisition so that 3) the banks can show the transaction to be less leveraged, especially if they are committing capital to fund the transaction; and 4) because the company often gets to use the adjusted EBITDA figure on its covenants, which provides more freedom but weakens the covenants.

Analysts have to look at these add-backs and decide how much credit they want to give for these anticipated cost savings. They also have to determine if there are offsetting cash expenses that are needed to accomplish these cost savings that are not being included in the figures, and then derive an adjusted EBITDA figure. However, this is just the first step. Analysts have to try to determine what others in the market are giving the company credit for in the add-backs. For example, in a new loan offering, analysts may believe the company should get credit for only 75% of the add-backs and this is what they base their analysis on. However, if everyone else buying the loan is giving the company 100% credit for the add-backs, and one year later, the company has accomplished only 75%, the analysis may have been right, but the loans will likely trade down as other buyers are disappointed with the results.

Another problem with add-backs is that they need to be utilized to determine if the company is meeting its covenants. Often the company can use its adjusted EBITDA calculations for the covenants, but it does not have to disclose all the details publicly, which can make the analysis of these expected cost savings more difficult. In many cases, the bank covenants don’t just allow these add-backs one time; they can be used in the future too, if the company chooses to make more acquisitions or believes it can get more cost savings, which means it could make an acquisition with more leverage and use add-backs that show an inflated EBITDA.

Overall, adjusted EBITDA by itself is not a problem. Concerns arise if the adjustments are not fully disclosed and if they are abused.

WeWork

IPerhaps the most vivid example of the abuse of EBITDA is that of WeWork. In the interests of full disclosure, I was a client of WeWork for about five years (leasing office space) and I was very satisfied with the arrangement. However, the business model of WeWork was flawed. For an interesting exploration of the WeWork saga, the reader is referred to Billion Dollar Loser-The Epic Rise and Spectacular Fall of Adam Neumann and WeWork by Reeves Wiedeman, published by Little, Brown, and Company, 2022. On page 233, the author notes that in preparing its prospectus for an IPO, it came up with the term “Community Adjusted EBITDA” in which it made various add-ons which increased EBITDA by over $1 billion. They removed certain legitimate costs such as design, marketing, and various administrative expenses in what was obviously highly creative accounting.

They made these adjustments utilizing highly questionable assumptions and were widely ridiculed for the term “Community Adjusted EBITDA” which they then changed to the more neutral sounding “Contribution Margin.” The IPO was drastically reduced and WeWork was able to raise a reduced amount of equity in 2019. This, despite the fact that WeWork was showing massive and increasing losses on a GAAP basis. Not surprisingly, WeWork subsequently filed for Chapter XI bankruptcy. Through the magic of the bankruptcy code, WeWork had another IPO in October of last year, this time with much more conservative expectations.

At the time of the original IPO in 2019, a senior professor at Harvard Busines School wrote a paper titled “Why WeWork Won’t.” This 23-page analysis digs into the numbers and comes to the conclusion that the more that WeWork made in revenues, the more that it would lose. The latest fiscal year figures at the time showed that expenses of the company were twice as much as revenues. For the first six months of 2019, the author calculates that the company’s Contribution Margin of $340 million should have been adjusted to a negative $543 million. The author states (page 7 of the report): “Thus, the positive ‘Contribution Margin’ impact only lasts as long as the Company continues to receive rent concessions on newly leased space as long as they can continue to increase rents on their membership renewals. As WeWork mentions in the Prospectus, they are moving into new markets where upfront concessions are not the market norm. The potential impact of not receiving these upfront concessions on their Contribution Margin and their increased need for cash is not discussed.” Furthermore, on the same page: “WeWork does not include the impact of its corporate G&A (i.e., general and administrative expenses) on its net Contribution Margin, which under GAAP is included when calculating EBITDA. This is perhaps one of their more troubling omissions.”

WeWork imploded in 2019 and went bankrupt. Ironically, it was only the pandemic in 2020 which brought it back to life. Flexible leases suddenly became important. Let’s hope that WeWork this time around is more careful in how it reports its adjusted EBITDA, no matter what name it gives to it.

REIT Case Study

In recent years, I was involved as a consultant in a situation where a publicly traded REIT (Real Estate Investment Trust) was accused of manipulating its cash flow from operations. This metric is similar to EBITDA but is called FFO (Funds from Operations). FFO, like EBITDA, can be adjusted to AFFO (Adjusted Funds from Operations).

In this particular case, the company and its management were accused of the following:

-

Understating normal expenses by instead labeling them as non-recurring merger and acquisition expenses. These expenses were recurring because the company was constantly engaged in M&A activity as part of its growth model.

-

Other so-called unusual expenses (which were also recurring) were likewise not counted as expenses in calculating AFFO.

-

Expenses paid to affiliates were not included as expenses.

-

Methodology for calculating AFFO was changed from one year to the next making it appear that AFFO had increased in the latest year.

-

Management compensation was paid by the company through transfers of funds to an affiliate which understated the company’s expenses in calculating AFFO.

Senior management compensation arrangements were tied to AFFO which gave management every incentive to find ways of increasing AFFO. Because AFFO is a key metric, the improper increases in AFFO increased the company’s share price making it “cheaper” to buy other companies by paying for these acquisitions with the inflated shares.

The accounting firm auditing the company’s books was also the auditor of various affiliated company thereby bringing up questions about their independence. Also, the underwriters claimed to have no idea that numbers manipulation was going on. Likewise, the independent Board Members claimed innocence. Nobody wanted to see what was really going on.

Addbacks have become more prominent and pronounced in the Age of Covid

On May 20, 2020, the law firm of Proskauer Rose published an article entitled “The Impact of COVID-19 on Adjusted EBITDA.” (See www.proskauer.com/alert/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-adujsted-ebitda). It stated that “…adjusted EBITDA is ubiquitous in many credit agreements, and a higher adjusted EBITDA relative to a static level of debt allows a borrower to meet financial maintenance covenants and maintain the flexibility to take certain actions under their credit agreement…….Credit Agreements typically permit an addback to adjusted EBITDA for extraordinary, non-recurring and unusual costs, expenses and losses.” What is not allowed as “add back” expenses (based on SEC regulations and guidance) are those which are not incremental to and separable from normal operations of a business. These non-permissible expenses could include paying idled employees’ rent and other recurring expenses, excess capacity costs expensed in the period due to lower production and paying employees for increased hours required to perform their normal duties.

In addition, lost revenues associated with Covid-19 are not generally added back in coming up with adjusted EBITDA. “Add backs” must be evaluated on a deal-to-deal basis. “As a general rule, credit agreements only permit amounts to be added back in the calculation of adjusted EBITDA to the extent they were deducted in the calculation of net income under GAAP. Lost revenue generally does not qualify as an add back. This is because the idea of lost revenue does not exist under GAAP as an element of net income. “Revenues are either earned or recorded on the income statement or not earned and altogether outside the realm of net income under GAAP.”

Proskauser recommends that lenders should review the calculations carefully included in compliance certificates with a critical eye. It is important that add backs be legitimate, verifiable, and appropriate.

Fitch Ratings notes that EBITDA addbacks are sometimes capped in loan agreements as a percentage of EBITDA, usually from 5% to 25%. In recent years however, Loan Agreements have been loosened so that now the percent of loans with uncapped EBITDA adjustments is over 50%. (See November 18, 2021 article in Fitch Wire entitled “Pandemic-Era EBITD Addbacks Support US Leverage Issuer Flexibilit” www.fitchratings.com/research/corporate-finance/pandemkc-era-ebitda-addbacks-support-us-leveraged-issuer-flexibility-18-11-2021).

Covid-19 and Adjusted EBITDA

The onset of Covid-19 has led to massive disruptions in business which have negatively affected revenues and have led to the incurrence of extraordinary expenses. In such cases, it is understandable and appropriate that adjustments need to be made to EBITDA. The purpose of adjusted EBITDA is to come up with a “normalized” result of cash flow from a company’s business. What happened as a result of Covid-19 was anything but normal. Supply chain disruptions caused increased costs. Revenues for many companies plummeted. In some cases, appropriate adjustments are obvious; in other cases, the adjustments are judgmental; and, in additional cases, adjustments arise from negotiations between borrowers and lenders as permitted in credit agreements.

The obvious adjustments are generally extraordinary, nonrecurring or unusual expenses. The less obvious ones include the following:

-

Lost Revenues- this is very tricky because it is almost impossible to come up with a figure to support revenues which have been lost, especially with government support programs in many cases making up to a large degree for lost revenues.

-

Rent concessions- how are these handled? A normalized situation assumes that the company pays full rent.

-

Restructuring costs- as a result of Covid-19, many companies may have been forced to get rid of leases; and also lay off workers in which severance pay is involved. How exactly can you “normalize” these items?

It is obvious that a lot of judgment and guess work is involved, and any adjustments need to be explained and justified.

How accurate have the adjusted EBITDA metrics been? An answer from S&P Global Ratings

In a new report issued on February 8, 2022, S&P Global Ratings has come to the following conclusions (see “EBITDA Addbacks Continue to Stack”

Key Takeaways

-

EBITDA addbacks remain on an upward trend, with addbacks for deals originated in 2020 representing 31% of management projected EBITDA, and over 66% of last-12-month reported EBITDA in our sample of large mergers and acquisitions and leveraged buyout transactions.

-

Our analysis continues to confirm that marketing EBITDA (including addbacks) generally does not provide a realistic indication of future EBITDA and that companies also consistently overestimate debt repayment.

-

Together, these effects meaningfully understate actual future leverage and credit risk, and contribute to incremental event risk, as many covenant baskets are tied to EBITDA.

-

Actual leverage continues to fall significantly short of management projections (from deal inception). The 2018 cohort of deals, added in this report, on average, reported actual net leverage of 4.6 turns and 3.5 turns higher than that forecasted for 2019 and 2020, respectively.

-

Aggressive earnings projections were the principal culprit in the large leverage misses, with reported EBITDA coming in at 36% below marketing EBITDA in 2019 and below 39% in 2020.

S&P Global Ratings' fourth annual analysis of EBITDA addbacks finds most U.S. speculative-grade corporate issuers continuing to be unable to achieve the earnings, debt, and leverage projections presented in their marketing materials at deal inception. Of particular interest was whether EBITDA adjustments were an accurate picture of future earnings, with the answer remaining a resounding no.” (Emphasis added).

What is the solution to EBITDA abuses?

At the beginning of the Cult of We, the authors quote the famed economist John Kenneth Galbraith in his book A Short History of Financial Euphoria: “Built into the speculative episode is the euphoria, the mass escape from reality, that excludes any serious contemplation of the true nature of what is taking place.” (See Cult of We—WeWork, Adam Neumann, and the Great Startup Delusion by Eliot Brown and Maureen Farrell, Random House, 2021).

It is obvious to any impartial observer that even supposedly highly sophisticated investors are subject to bouts of euphoria. Books have been written about this. It seems to me that we need regulations that require accounting firms to not only give an opinion on GAAP measures but to also give an opinion on commonly used non-GAAP measures, EBITDA being the most important non-GAAP measure. There should be strict methodologies that need to be followed promulgated by regulators such as the SEC. Auditors are not allowed to opine on non-GAAP measures when they issue their Opinions. I believe that a strong case can be made that they should.

A Specific Proposal

-

The relevant accounting bodies and the SEC should agree on a detailed and appropriate methodology for calculating EBITDA and adjusted EBITDA. This detailed methodology would then become part of GAAP, Generally Accepted Accounting Principles.

-

In certain matters, an element of judgment may be required in permitting adjustments. The auditor needs to be certain that such adjustments are not misleading or dishonest. Also, the Audit Committee of the Board of Directors has to be fully involved and likewise convinced that the adjustments are not misleading or dishonest.

-

This proposal recommends that when auditors prepare the financial statements, they need to state that the financial statements have been prepared in accordance with GAAP and that furthermore, any important but hitherto non-GAAP metrics, such as adjusted EBITDA, have been prepared in accordance with GAAP.

-

Furthermore, in recent years auditors have been compelled to comment on Critical Audit Matters (“CAM”) which come up during the course of an audit engagement. Under CAM, the auditors explain difficult, subjective issues that they have encountered in coming up with an audit that they opine has been done on the basis of GAAP and with no material misstatements. I believe it should be imperative that CAM discussions should include comments on adjusted EBITDA especially those adjustments where an element of judgment is required.

There have been too many situations where accounting firms have said that opining on non-GAAP measures is not their job. There should be no excuse for this in the future. Calculations of EBITDA and adjusted EBITDA and related methodologies need to become part of GAAP. The auditors need to opine on EBITDA and adjusted EBITDA calculations.

Summary and Conclusions

Whether we like it or not, adjusted EBITDA has become perhaps the most important figure used by companies to demonstrate their credit worthiness. Companies are sold at prices determined by a multiple of adjusted EBITDA. Rating agencies rate debt issues and companies on the basis of Debt/adjusted EBITDA. Investors make investments on the bases of these leverage ratios and on the basis of ratings. We need to make sure that the methodology employed in calculating adjusted EBITDA can be relied upon and that accounting firms can opine that adjusted EBITDA is arrived at in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles and is not misstated or misleading or fraudulent. It is time for adjusted EBITDA and other important non-GAAP metrics to become, once and for all, GAAP metrics.

Anything less than this should not be acceptable to the regulators, the Board of Directors of a company and to the creditors and investors. It is time to end the abuse of EBITDA.

The regulators and the accounting profession need to understand this very simple fact: THERE ARE TWO TYPES OF PROFITS, CASH AND ALL OTHER KINDS. ACCOUNTING PROFITS WILL NOT PAY THE RENT. The business community and many investors understand this very well as do Professors of Finance. Many non-GAAP measures including EBITDA and adjusted EBITDA are honest attempts to bring accounting back down to Earth. These non-GAAP measures are important and need to be treated as important by the accounting community and by the regulators. This paragraph captures the essence of my comments in this article. We can no longer ignore EBITDA and adjusted EBITDA. They must be subjected to greater scrutiny utilizing an agreed-upon- methodology and they must become GAAP metrics subject to intensive review by auditors. Anything less is no longer acceptable.